On Being Asian-American/A Noodle Soup Addict

/Is this post just about food, or does it have some nuance? You be the judge.

Nobody gives you a manual on how to be the child of immigrants. Your parents, if they arrived as students to the United States as mine did, may have received a pamphlet at an orientation meeting about life in their new country. We, their children, however, get no such document. Instead, we are born straddling two worlds and left to figure out how to navigate both.

The country we grew up in is the easier one to manage. After all, it is home. Born and raised in Ohio, I assumed the Midwestern life: eating unhealthy foods, playing outside with the neighborhood kids, and staring at the tv for hours every day. If you grow up as I did in an area where there aren’t many people like you, you identify with the majority culture. Of course there were times when I was told that I didn’t actually belong, based on my name, appearance, or some other superficial indication. And immigrant parents sometimes imply that you don’t entirely belong, in a subconscious effort to cleave you to their beliefs, which are increasingly incongruent with the world that you know best. Despite these moments however, I knew that I belonged here as much as anyone else. As a child, my patriotism flared fierce anytime someone challenged my identity. When asked where I was from, I stood my ground. I am an American, and I am from Ohio. Final answer.

Halloween with the neighbors.

The other world, the world from which your parents came, is more of an enigma. Its influences are undeniable, embedded in your DNA and the way your family raised you, fed you, and taught you. However, these old world influences are overshadowed by the more familiar ways of the home country, so they recede to a dark file cabinet in your consciousness. How many of us were forced to go to Chinese School on weekends, suffering through hours of seemingly pointless class and retaining nothing? How many of us know nothing about the history of the country from which our parents come came? Despite the Cultural Revolution being responsible for the mass migrations that ultimately led to my soul being deposited on American soil, I was probably in my twenties when I read any more than a few paragraphs about it in a world history textbook.

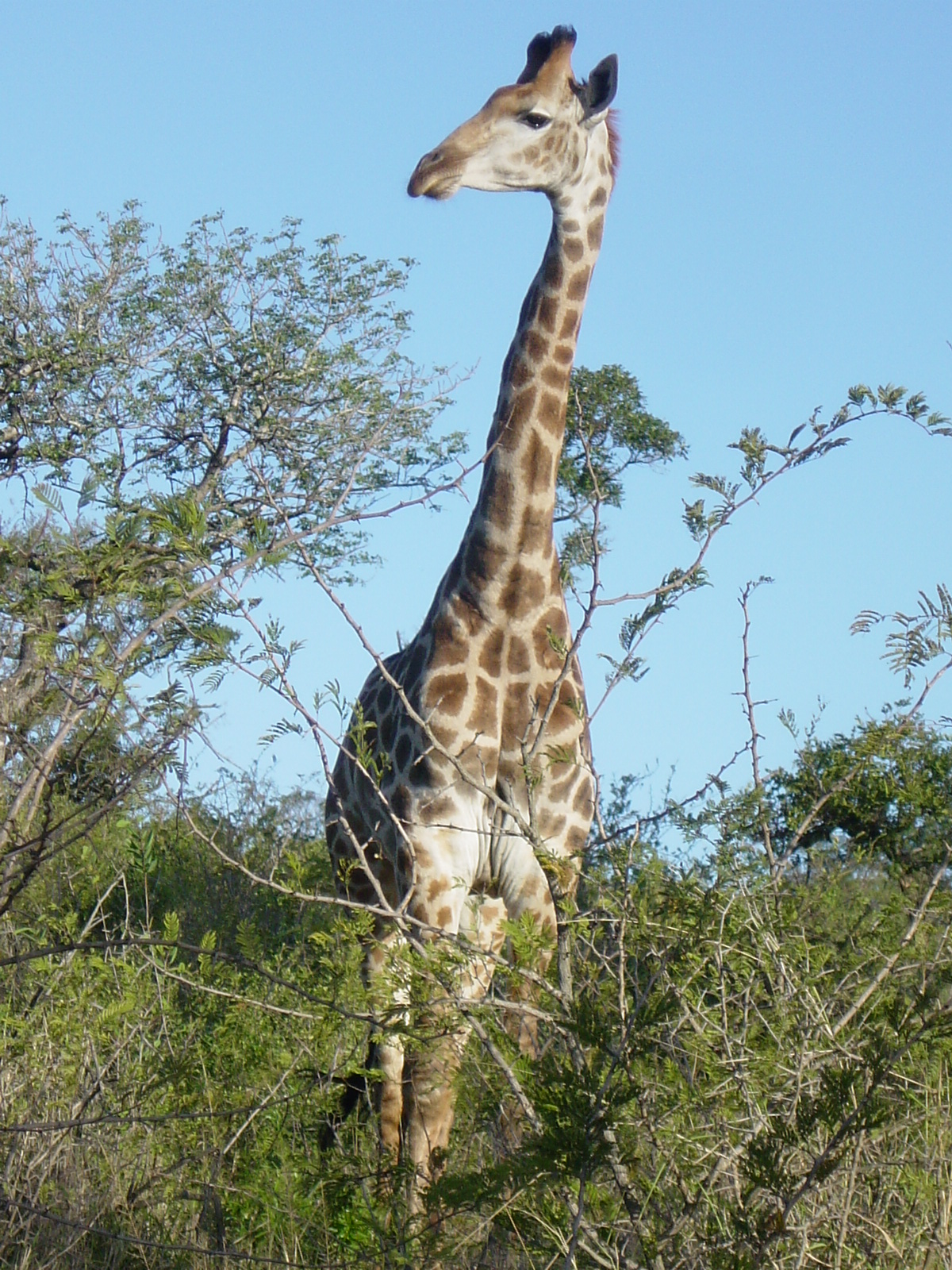

Something about this guy.

For me, the enigmatic old world is Taiwan, where my parents were born. While growing up, I visited Taiwan only twice: once when I was three and once when I was 12. The trip when I was three consists of very hazy scenes viewed from the height of a chair seat. I remember the air being damp and surfaces sticky, and I remember the sounds of street peddlers in the early morning. I also remember going to this day school that I absolutely hated. The kids at the school, upon finding out that I was from the USA, showed genuine horror, exhorting me not to go back because all the people with all the guns would certainly shoot me dead (some things never change, huh?). Apparently I cried every day until someone came to pick me up. Attending American preschool was fun, but trying to fit into this one made me miserable.

Although often hidden, these old world influences are prone to come out at strange times. At one point in middle school, I slapped my Sanrio eraser onto my face in utter boredom or exasperation, and I realized at that very moment that it smelled like Taiwan! The eraser smelled like Taiwan! It took me decades to figure out why. One day in an Asian grocery store, I rediscovered the Yakult drink, these yogurt drinks that come in insulting small sizes. Seriously, as an adult, it’s barely enough to wet your tongue, but as a kid, it was a wonderful treat. And then I made the connection - the eraser smelled sweet and slightly cultured like this drink!

It makes sense that, as a child, smells and tastes constitute your strongest consciousness of the old world. Before you can understand the hardships your parents endured, the challenges they faced, the training and education they craved, and the sense of greater opportunity they longed for, before you can understand all of this, your nose and your stomach tell you about your parents’ past lives. From the earliest age, you understand that food and drink mean home.

As a kid, I grew up on awesome home food and drink. My mom is an excellent cook, and her side of the family is in the restaurant business. My uncles, once fine chefs in Taiwan, run a vastly under-appreciated Chinese restaurant in Ohio, where they make gourmet dishes for Midwesterners who would just as happily go to Panda Express. Once in a while they’ll carve an exquisite bird from a carrot or turnip just because they can, and because it only takes so much skill to fry crab rangoons. In this environment, I grew up a bit of a Chinese food snob, which means I get pretty grumpy when I am forced to eat non-Asian or sub-par Asian food for long stretches of time.

So it is no surprise that my trip to Taiwan at age 12 featured some delicious eats. I remember the warm pineapple buns from the bakery down the street, the papaya milk from the convenience stores, the seafood at fancy restaurants, the freshness of the vegetables everywhere. My family lived right off of Yong Kang Street, which is FOODIE CENTRAL in Taipei (and aren’t all Taiwanese foodies?), so you could trip out the door and have the meal of your life. They lived right off of the triangular-shaped park near one end of the street, which was the starting point for all of our tasty expeditions.

My favorite food, however, was easy to find - right at the corner of the park. There, beef noodle soup awaited me every night. At that corner, an old man sold the dish from his rickety steel cart piled high with bowls, which seemed barely rinsed. Basically, the options were a small or a large bowl. Once you ordered, he would slap in the soup and the noodles and the beef (so tender) then hand the steaming bowl immediately back to you. As a kid that soup was so spicy to me but also so addictive. We went so many times, I got used to my mouth burning and my skin damp as we stood in the night air amongst the hordes of Taiwanese people. It was always worth it. Back in the States, I’ve tried all kinds of versions of beef noodle soup in an attempt to relive the satisfaction that came from one bowl of that street stall. I even try making it myself, tweaking my mom's recipe to my tastes. But nothing has ever come close to the real thing. In the futile attempt, I have become a noodle soup addict. How can a bowl of hot goodness be so comforting regardless of the ambient temperature?

The park today. Seems cleaner than I remember.

Fast forward to last summer. I had unwittingly chosen as my life partner a non-Taiwanese violinist in a quartet with serious Taiwanese roots. He went more regularly to Taiwan than anyone I knew. I decided to join him last year on one of these quartet trips, as an excuse to experience the country as an adult and to see my family. Once there, I expressed to my uncle a desire for good beef noodle soup and he, perhaps jaded by long exposure to the treasure, shrugged and agreed to take me to a famous place. At a bustling noodle shop just off of Yong Kang Street, we waited in line not too long before being seated upstairs at a large round table with other diners. The interior was cafeteria-like and not at all fancy, but there was a convivial feeling in the air. Each of us ordered the house beef noodle soup, and when it arrived, my family commenced slurping it as if it were just another meal. I took my time smelling the broth and scooping up a spoonful, fully expecting to be disappointed. Then I put the spoonful in my mouth -- and something magical happened: my memory was sent spinning into a time warp. Here in this dark, rich spicy broth, was the exact same flavor that I had had at that cart near the park decades earlier. All of a sudden, I was back there, the same night air on my skin; in my mind, the constant annoyance of a preteen, the discomfort of being in a foreign land, and the discovery of my relatives as strangers and yet family. It all washed over me in a fraction of a moment.

Now the literary among you will read this and call to mind the famous madeleine moment in Proust’s masterpiece, Swann’s Way. I cannot hope to describe this moment with any similar facility, but I’ll tell you that my beef noodle soup moment was just like Swann’s madeleine moment. One mouthful of soup sent me hurtling on a journey of memory that unearthed long-buried memories like an industrious squirrel recovering nuts. The familiarity of the soup was strangely emotional. It was as if I had returned to a place that I did not know I had left. The intensity of the moment told me that I too was of Taiwan - that the country was somehow embedded in my being, even if I hadn’t yet organized its influences. I paused, spoon in midair, mouth agape, marveling at what just happened as everyone around me slurped onwards unawares. My uncle later told me that this restaurant was opened by the old man with the cart and a business partner who later backstabbed the old man and took over the enterprise after learning the old man’s secrets. After being ousted, the old man apparently went back to the corner of the park to restore his stall, but it was too late. At this point, the restaurant has outlived the old man. A sad story that explains why the soup was so familiar.

The magical soup.

After years exploring Asian-American identity, I still don’t fully understand what it means to concurrently inhabit two worlds. But for me, the old world soul of an immigrant's child is like that sip of soup. The collective experiences of our forebears are all there in us somewhere, subtle and intermixed like the flavors of a secret recipe. And it can take a while for those influences to emerge. We start with sensory triggers and hopefully move on to more intellectual probes of the old world. I'm now in my second consecutive summer of discovery in Taiwan, and I'm grateful for these opportunities to deepen my understanding of this place. I now appreciate much more - not just its culinary riches and natural beauty but the social structure that has put in place stronger infrastructure and healthcare systems than in my home city, and the ways in which people treat each other with warmth and generosity and hospitality.

It has been personally beneficial for me to acknowledge my dual identity and not suppress one or the other, but on a national scale this is critical. Recently in my home country, groups of people who believe in one supreme identity have come into the open, brandishing their symbols of exclusion and violence against people unlike them. As someone who is 110% American, I feel a duty to validate the non-white portion of myself and the immigrant struggle that gave me the opportunities I have, as a way of celebrating this country that I love so much. At the same time, for perhaps the first time in my life, I am fearful that my home country will finally lose sight of diversity of identity as an invaluable thing. These days, I’m clinging to my soup, hoping that we come around.