Bach, Glorious Bach

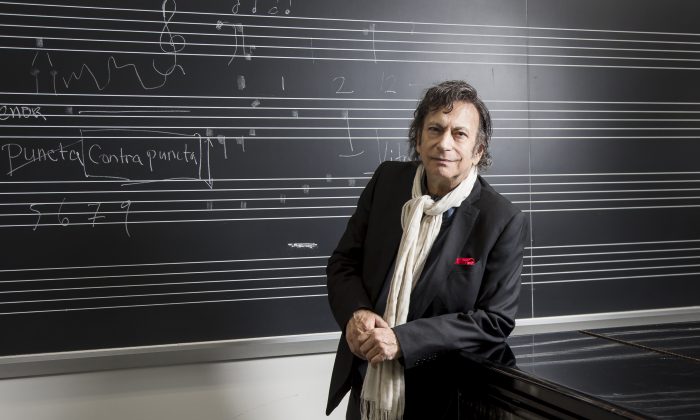

/Photo by Jiyang Chen.

What happens when you steep yourself in Bach? Do your fingers and toes turn pruny and then start to write counterpoint? Audiences in NYC and the Bay Area will soon find out when violinist Wayne Lee and I present Bach's complete sonatas for violin and keyboard starting December 1 and 2! Join us if you can!

For the NYC series, I wrote a guest post about the wonders of steeping in Bach for Listen Closely, the community-based chamber music series presenting the concerts. Read this post on Listen Closely's website, or full text below.

-

For most people, the word “immersion” probably conjures up language learning, infinity pools, and blenders. It is less likely to conjure up a concert experience - after all, musical programming these days often offers a dizzyingly diverse array of styles. Which is great.

So, color me skeptical when two years ago, Wayne Lee decided to play all of J.S. Bach’s six works for solo violin over two concerts, presented by Listen Closely. My skepticism had two roots. First, the Bach solo violin works represent the pinnacle of artistic and technical writing for the instrument. There’s a good reason one is required for almost every violin audition and competition. The study of even one of the six can occupy a musician for years. To do all six at once? Crazy.

My second concern was as an audience member. Two concerts of just one type of composition by one composer? Would I get bored? Would it all sound the same?

After attending both concerts, I am happy to report that my fears were completely unfounded. First of all, Wayne Lee is an absolute violin beast, with a rare musicality and depth of insight that shows in everything he plays. After one concert, an audience member remarked that, usually when he listens to performances of these pieces, he hears how hard they are. When Wayne played them, all he heard was music.

Secondly, as an audience member, the immersion experience revealed more than I thought possible. By listening to six distinct works of Bach over two evenings, I began to internalize his style, to hear increasingly more detail, and to dwell more fully in the moment of the performances. The best way I can describe it is that it was like a road trip - at first you’re aware of everything but the journey: did we pack enough beef jerky? Which exit are we looking for? Did someone call Auntie Jane to tell her we’d be 4 hours late? But after a while, you settle into a rhythm and can watch the world go by. The longer you drive, the more you notice the diversity of landscape. When I was a kid, we drove across the United States, and I remember watching in wonder as the plains became the Rockies became the salt flats became the coast. In Bach, the landscapes are equally distinct and awe-inspiring. After a few minutes into Wayne’s cycle, I began to discern Bachian soundscapes - poignantly beautiful laments, vivacious celebrations, and heavenly visions. By the end of the concerts, I was listening completely differently. I was IN the world of Bach, and each nuance, each change of pace, was more meaningful than it had been in the beginning. It was a transformative experience.

Because of those solo Bach concerts, it was an easy decision to do this cycle of complete Bach sonatas for violin and keyboard. Bach is the perfect composer for performing cycles, or a series of concerts focused on a type of work by one composer. He wrote so many works in groups of six: the solo violin sonatas and partitas, the cello suites, the Brandenburg concerti, the English suites, and on and on. As the master composer that he was, he explores the full potential of each category - they feature as much diversity within each work as between works. It seems six was the magic number - by the sixth work, Bach had both defined the boundaries of the genre and systematically defied them.

These six violin and keyboard sonatas also exemplify that mastery and creativity. Although they mostly follow the same 4 movement formula - slow-fast-slow-fast - there are surprises everywhere: a fifth (solo!) movement! A presto movement! An über-chromatic movement! Clearly, these sonatas were not the mindless exercises of a composer rushing to publish. Bach imbues every moment of his deft counterpoint with the highest form of his art.

But even if you don’t notice all of the points of compositional mastery, you can enjoy such a cycle because, ultimately, we love Bach for his profound beauty. Given that fact alone, an immersive experience in Bach can be as rewarding as learning a new language, as relaxing and invigorating as a good swim, and as good for you as a blended smoothie!

These sonatas are some of the most wonderful works written by Bach, and the challenges posed by playing them on modern instruments is well worth the reward. We hope you will come with us along for the ride. Enjoy the view!